By Jeremy Gluck for GS Artists

National Portrait Gallery

Punk rock? You know it when you hear – and see – it; months before I heard the debut Ramones album I had put pictures of them from Rock Scene on my wall. I knew. And I was right: the Ramones possessed life-changing powers. They sure as hell changed my life. A friend of mine went to London in 1976 and sent me back a parcel of punk singles, among them the Sex Pistols’ Anarchy in the UK; the first time I listened to it it was too alien to absorb, but the second time I looped it over an entire C-60 cassette I listened to obsessively for weeks.

Punk is still the music anybody can play, a dream you can have when you’re awake: everybody dreams but it ends when you awaken, whereas for me and many others punk was in its prime a dream we shared while awake. Its energy and ethos have its roots in things as unlikely as the Beats and Warhol, mass production and mass media, which it both rebelled against and benefited from. Punk represents freedom of identity and creativity, a will to take chances, make things for the sake of it and wreck things for the fun of it. As manifestos go, that still works for me.

Punk is still the music anybody can play, a dream you can have when you’re awake: everybody dreams but it ends when you awaken, whereas for me and many others punk was in its prime a dream we shared while awake. Its energy and ethos have its roots in things as unlikely as the Beats and Warhol, mass production and mass media, which it both rebelled against and benefited from. Punk represents freedom of identity and creativity, a will to take chances, make things for the sake of it and wreck things for the fun of it. As manifestos go, that still works for me.

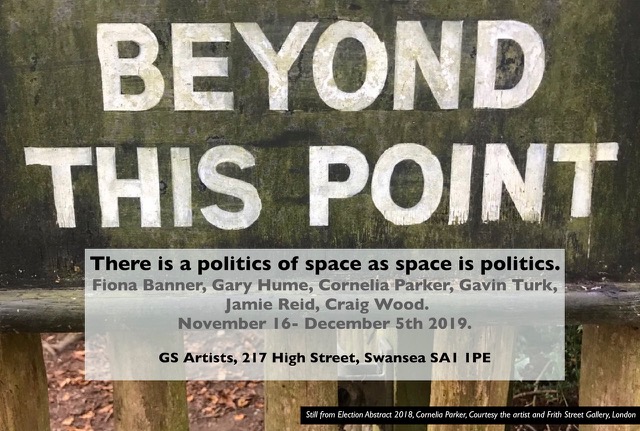

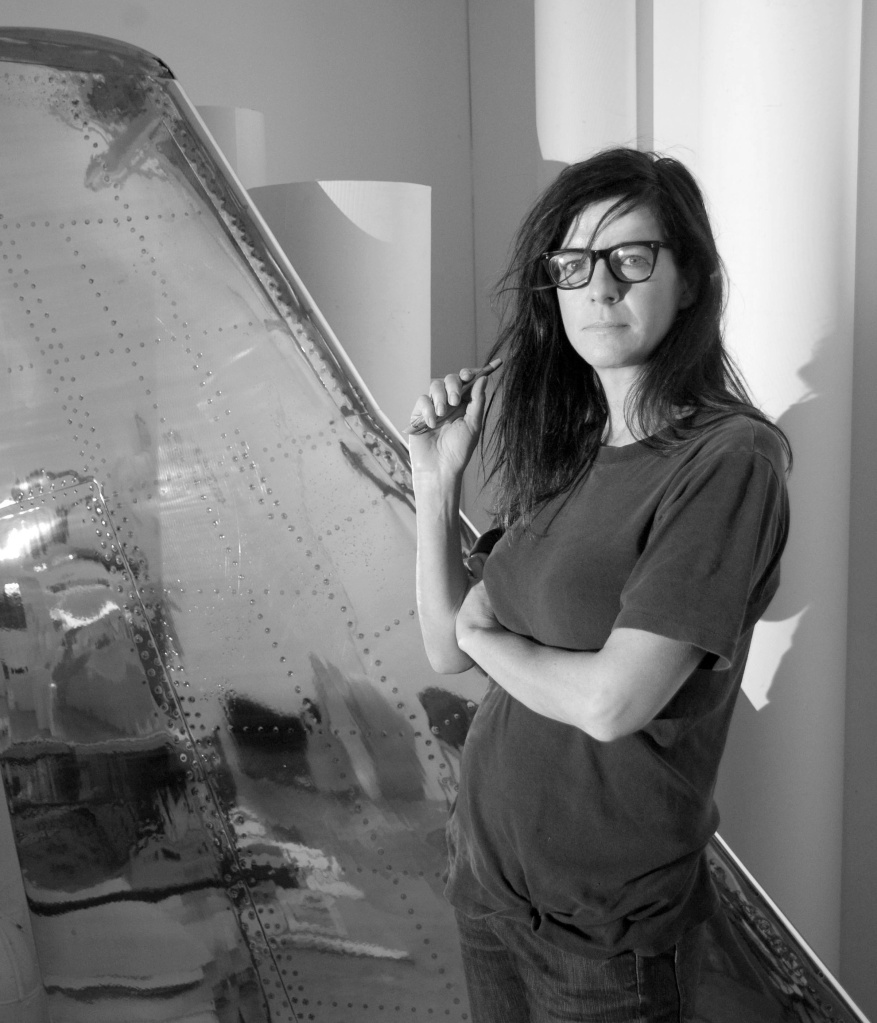

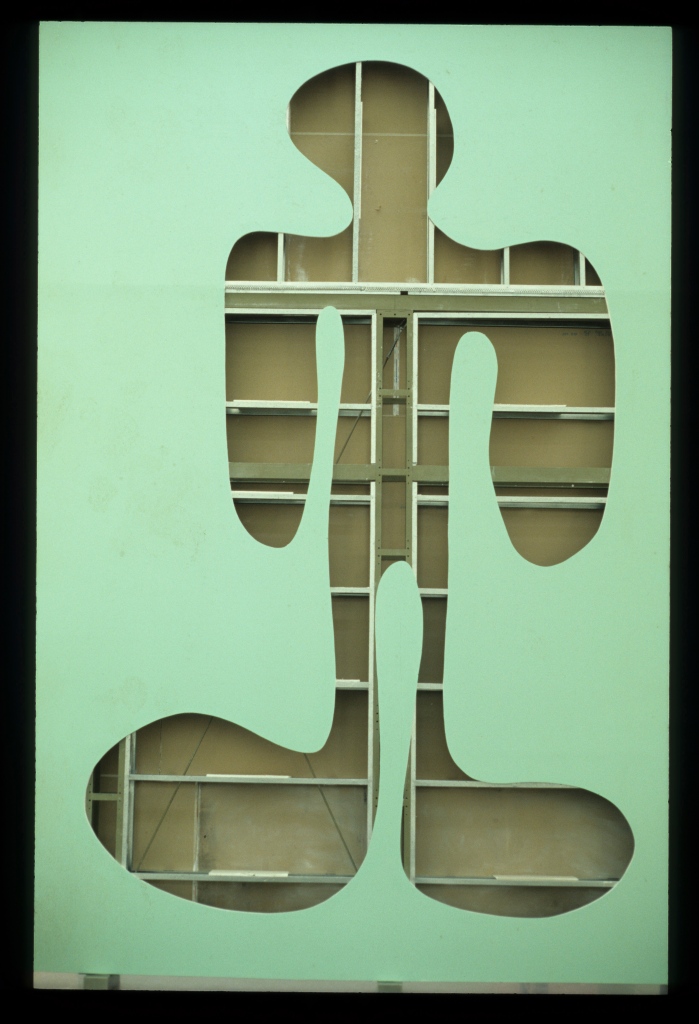

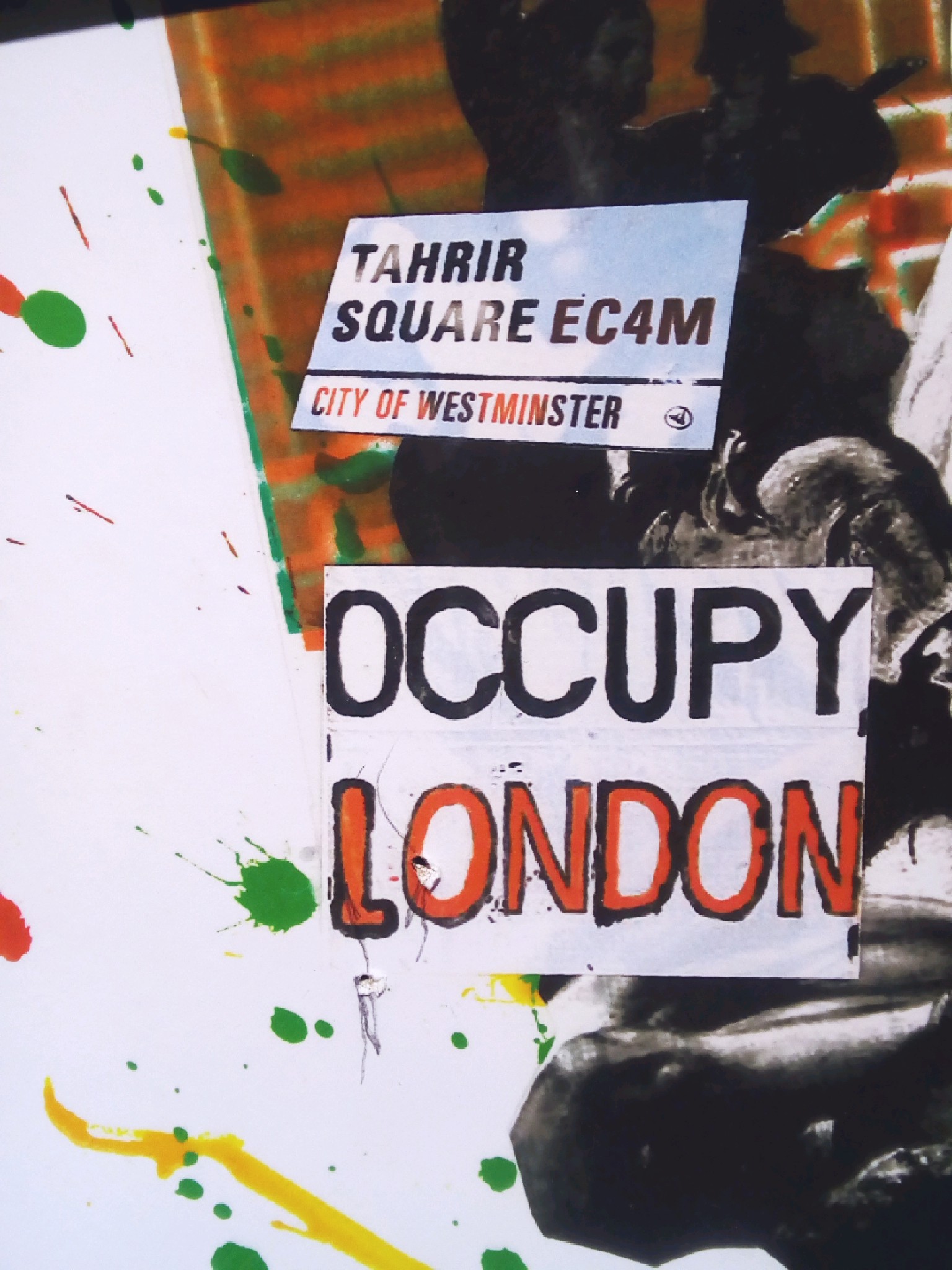

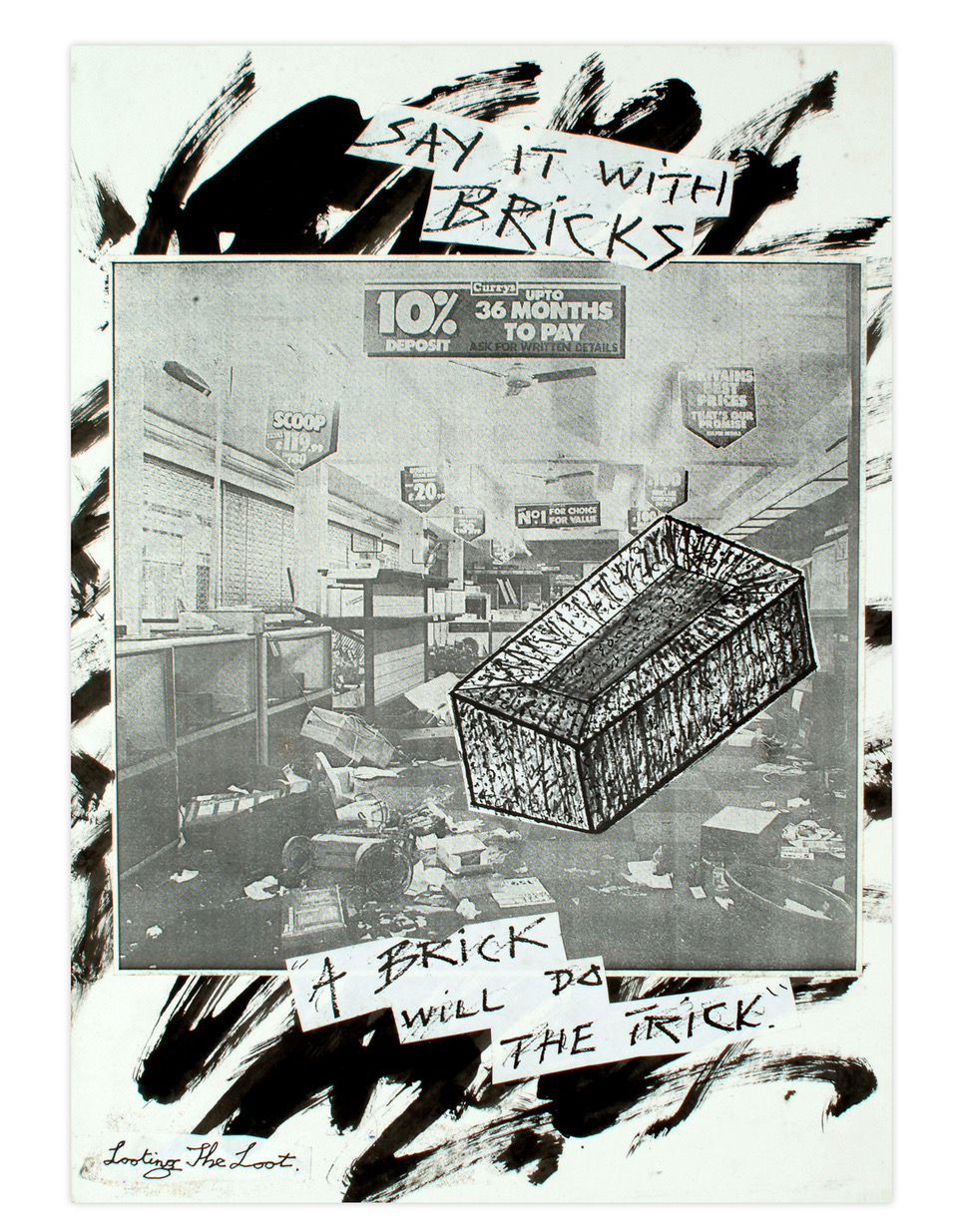

Jamie Reid, best known for his décollage covers of the Sex Pistols’ albums Never Mind the Bollocks, Here’s the Sex Pistols, as well as their singles including Anarchy in the U.K. and God Save the Queen, is a self-described anarchist, since creating cover art that helped define the aesthetic of the British punk movement working tirelessly at his practice, and as an activist and agitprop icon to move us all to face and facilitate changes necessary to our lives and world. At Croydon Art School his path crossed fatefully with future Sex Pistols manager and punk svengali, Malcom McLaren, and in harness they transformed the music and art. Represented by John Marchant Gallery in London, Reid’s works are in the collections of The Museum of Modern Art in New York, the Victoria and Albert Museum in London, and the Tate Gallery in London, among others.

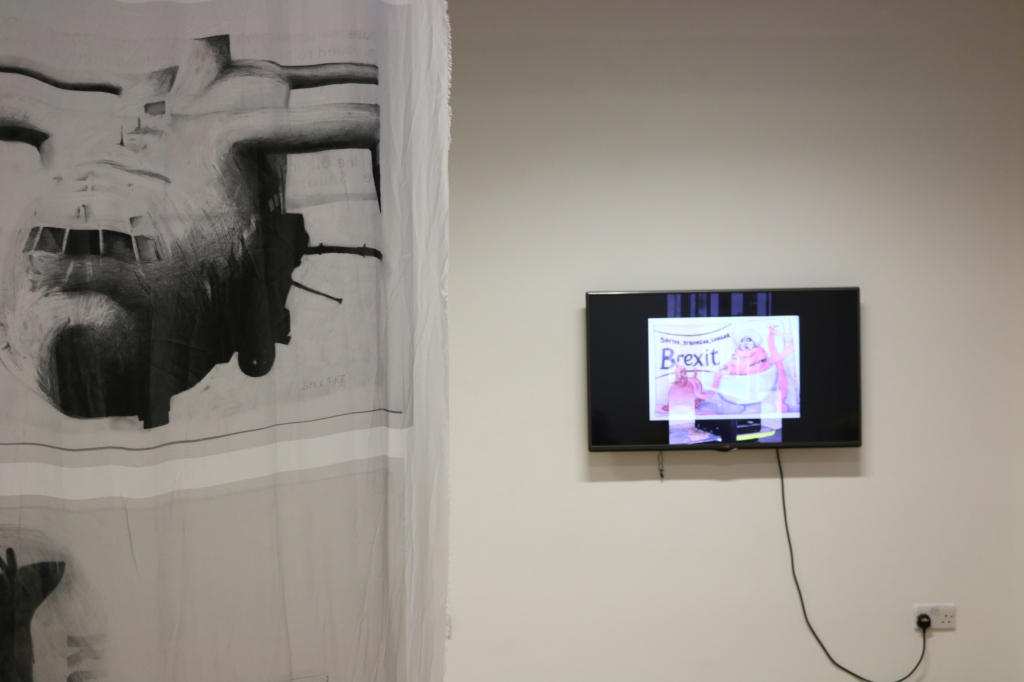

On the eve of his 2020 retrospective at GS Artists, Dragons Revenge, I interviewed Jamie Reid, at 73 still an iconoclast and highly political working artist. His passion for art, music, culture, ecology, spirituality and the predicament of humanity – and with his bedrock detestation of capitalism and conformity reassuringly evident – Reid proved an absorbing and eclectic subject the privilege of interviewing who will long remain with me. Not willing much to revisit the past – his own remarks on it here largely unprompted – he is by consensus one of the outstanding, most important British artists of his generation, one concerned with being as much as doing – and making – and so conferring on his output thereby the imprimatur of an integrity and humanity that is both astringent and moving. A remarkable man and artist, therefore, and one we should treasure for his resolve, audacity and vision. Toward the end of this interview Reid, exploring the loss to us of our knowledge of nature, claims he is “rambling”. “Rabelaisian”, more perhaps, by definition creating work that is “a metaphor for guerrilla civil revolt” and referring to people who “have become giants whose strength and appetite are enormous”. It’s just such a lust for revolt and life that characterises Jamie Reid, a man that – while shaping it – has been and still is of and in and out of his time.

On the eve of his 2020 retrospective at GS Artists, Dragons Revenge, I interviewed Jamie Reid, at 73 still an iconoclast and highly political working artist. His passion for art, music, culture, ecology, spirituality and the predicament of humanity – and with his bedrock detestation of capitalism and conformity reassuringly evident – Reid proved an absorbing and eclectic subject the privilege of interviewing who will long remain with me. Not willing much to revisit the past – his own remarks on it here largely unprompted – he is by consensus one of the outstanding, most important British artists of his generation, one concerned with being as much as doing – and making – and so conferring on his output thereby the imprimatur of an integrity and humanity that is both astringent and moving. A remarkable man and artist, therefore, and one we should treasure for his resolve, audacity and vision. Toward the end of this interview Reid, exploring the loss to us of our knowledge of nature, claims he is “rambling”. “Rabelaisian”, more perhaps, by definition creating work that is “a metaphor for guerrilla civil revolt” and referring to people who “have become giants whose strength and appetite are enormous”. It’s just such a lust for revolt and life that characterises Jamie Reid, a man that – while shaping it – has been and still is of and in and out of his time.

GS Artists: Your work changed the world of art and design. How does that feel?

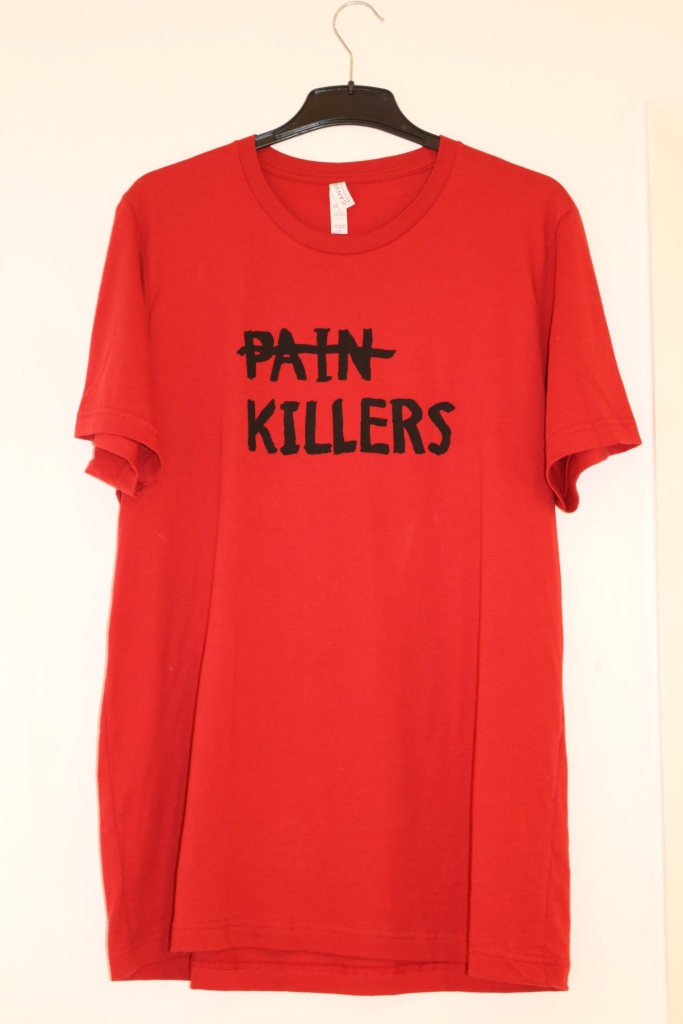

Jamie Reid: It depends on which ways it’s been done. I’ve just done a campaign against McDonald’s, who rip my work off terribly, and if it’s done by corporate people I hate it, but it’s fairly inevitable that things, in many ways creative arts and the establishment, are very sort of blameless and anything that comes up new they try to rip off to try and make money out of.

GS Artists: Sure, that’s true. That could be called our culture.

Jamie Reid: But if it’s done with some with intent, and with a sort of political message, I approve of it. It depends on how things are done. I mean, on a purely, sort of music level, someone who really understood where me and Malcolm McLaren are coming from with the Pistols and punk were the KLF and what they did, but they took it to a completely new generation.

GS Artists: Do you feel there’s anyone now taking it to a new generation?

GS Artists: Do you feel there’s anyone now taking it to a new generation?

Jamie Reid: There probably is, probably don’t know about it, probably worldwide there is. I mean the movement against global warming and the planet is fantastic.

GS Artists: It’s 2020. About a year ago I was in the aisle of a big superstore somewhere and it was empty, just this kind of void. And I posted it on Facebook with the caption Anarchy in the UK 2019. What is anarchy in the UK now? Brexit? After Brexit? Is there no anarchy? Have we lost all hope of anarchy?

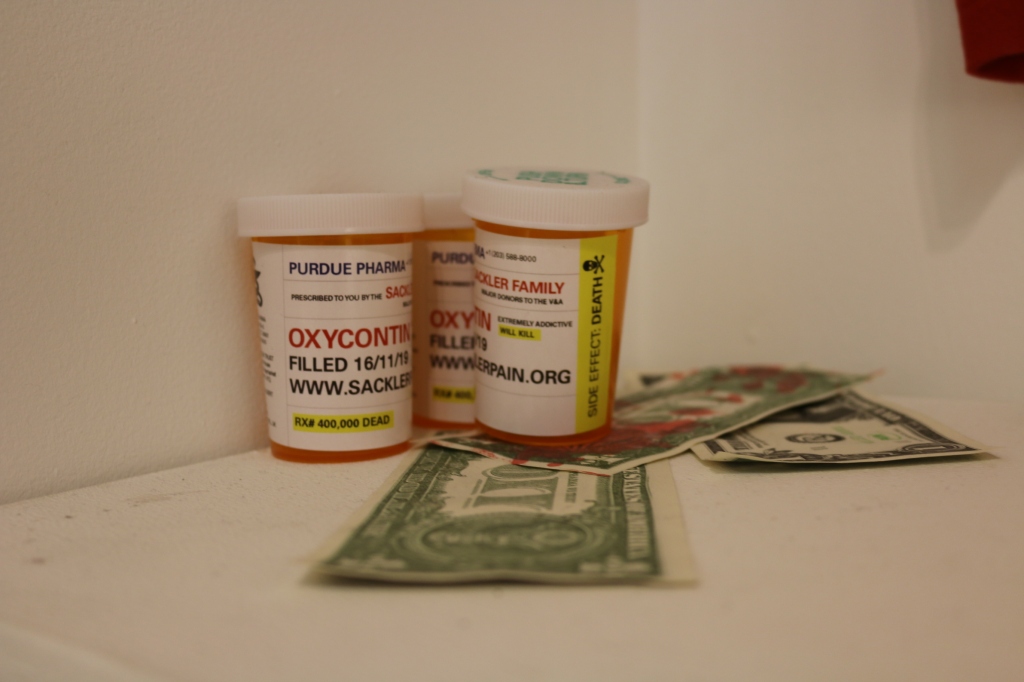

Jamie Reid: There are reasons why, there are many. It’s absolutely appalling what’s happened in this country, probably ever since Margaret Thatcher. You now got Boris Johnson, and without getting into legal trouble if you were to watch a film, Riot Club, about where his background comes from, The Bullingdon Club, the man is like a fascist rapist who – it’s not a direct quote of his but it’s an image I’ve done for the GS exhibition where he actually ends up saying, “We were born to rule over scum”. And he got voted for, but funnily enough he got voted for in a way Trump got in. Boris Johnson used the television appearing as a guest on various programs, like Have I Got News for You, and became popular playing a buffoon. Yeah, so brings me back to my starting point, which is a society of the spectacle emerging in a situation as politics and the society of the spectacle, which has been so proven right.

GS Artists: And there are people who can exploit that. With the Johnson phenomenon, these people have looked at Joseph Goebbels’ playbook. They’ve understood those principles of creating spectacle which the Nazis excelled at, for example. They’ve adapted it to the time, and to the audience, but there’s no mistaking there’s some sort of study going on there of that kind of manipulation. One of the images you’re exhibiting at GS is against English Heritage. What is the context for the protest?

Jamie Reid: It relates to my whole background; it was a very socialist but Druidic background. And the English Heritage in particular to me is the way they took over something like Stonehenge and the way they seem to represent everything that’s conservative and represent the worst of English history. Whereas, I suppose, one thing I’m really involved with is that we’ve got a whole unsaid, unrecorded history. That’s just a thing to get out there actually. With the present politics I was very taken with Margaret Atwood. I was trying to think of images for Boris Johnson and Trump and Putin, and she came up with a quote where she was asked what do you think of the present, the political situation, and she said we’re going backward at a very rapid rate (GS: A work citing this appears in the show). And then I suddenly saw from my end, Putin is the Czar, Trump is like the John Wayne cowboy, and Boris Johnson is a combination of Flashman and Tom Brown’s School Days and a Roman emperor. You know he’s obsessed with Roman history and that’s relevant as well…Roman history and Churchill, what a combination anyway!

E GS Artists: My next question is related to what you just said and about issues of the environment and your perspective on Extinction Rebellion and for example, Greta Thunberg, who I think is wonderful.

Jamie Reid: Yeah, I do…

GS Artists: What do you make of all that? What do you think is the context and provenance of it all, and its future?

Jamie Reid: At its worst, it’s Stormzy playing Glastonbury in front of 100,000 upper-middle-class white people. In principle Extinction Rebellion is fantastic. I work at a community center, which I’m totally immersed in, in Liverpool called The Florrie, The Florence Institute. And it’s one of the poorest areas in Liverpool and you ask those kids about the environment, they’re not remotely interested. All they are interested in is getting by day by day to survive, so you know to some extent, things like Extinction Rebellion come from a position of privilege. I totally agree with what they’re trying to do, but it’s got to come from below as well. The extent of poverty in this country is just unbelievable and pretty much unrecorded.

It’s actually relevant to me, this because, over the course of the last 30 years, I have done all sorts of lectures and talks to young people. And when I think about when I went to college – which is where I met Malcolm McLaren – I went to college with no 0-levels at the age of 16 and got a grant. When you think about what happened to education since then, you now have to pay nine thousand pounds a year, you know it’s unbelievable. Things like education were so fought for by early socialists and others and it’s unbelievable what we’ve done to education, it’s so relevant to what’s happening with the environment, I think. I know how they cut things like art and music and drama out of the syllabus in schools and you know they made schools including our primary schools competitive, and examinations, just awful. Education should all be about caring for your planet and caring for your fellow human beings. And it needs a complete re-think of education to make things okay.

When I was working at Suburban Press, which was a community press, I mean it’s so important because the look of it, the look of punk came out of what I was doing at the Suburban Press. And we were actually doing stickers, putting them up wherever we could, particularly in West End and Oxford Street was a sticker saying ‘Last Days’ (GS Artists: this graces the GS entrance for the show), a free sale going on here because the world’s running out of raw materials. We also did a sticker saying ‘This week only the store welcomes shoplifters’. I’ve been fighting on that whole campaign about the environment, it goes way back. We think it’s a new phenomenon but people have been fighting for it for hundreds of years. William Blake…

GS Artists: Well, indeed. I went to the Tate exhibition. Did you go to the exhibition in London?

Jamie Reid: No, I haven’t.

GS Artists: It was stunning.

Jamie Reid: I totally love Blake, I have such an empathy with him as well. It wasn’t really until the 1920s that anyone really got to know about him.

GS Artists: The Tate exhibition, I was literally rendered speechless. It was overwhelming. It was so beautiful and profound. I came out of it with my kids and we were all standing around in shock.

Jamie Reid: That happened to me with an exhibition that I went to see in Liverpool and there is so much unknown about art history…a woman artist called Leonora Carrington. She actually was born into the English aristocracy at the beginning of the 20th century, rebelled, hated it, ran away to Paris, where she totally fell head over heels with Max Ernst. And they had a fantastic relationship but because of the Nazis getting in and taking over in France they moved down to Spain, and I don’t know if Max Ernst got captured or something happened to him but they got split up. She ended up in a mental home in Spain but one of the doctors there took an incredible liking to her and he was Mexican, and he took her back to Mexico and in Mexico she is regarded as an incredibly important artist. She did fifty years of absolutely work there and it’s only recently here she has got any recognition. Which is just so true of so many women artists as well but her work just blew me away, it was fantastic.

The same with Blake, I went to the Tate at Millbank when I was about 15, 16 and it just blew me away along with Jackson Pollock anyway.

GS Artists: A good combination! One of my towering muses is William Burroughs. And of course, there is a sort of lateral line to be drawn if you want to draw one between something like Burroughs and Gysin cut up and then what became your dominant style, or at least the one year the most famous for, in my humble opinion. I have a wonderful Burroughs quote that I’m going to then supply a question to: “Out of the closets and into the museums, libraries, architectural monuments, concert halls, bookstores, recording studios and film studios of the world. Everything belongs to the inspired and dedicated thief…. Words, colors, light, sounds, stone, wood, bronze belong to the living artist. They belong to anyone who can use them. Loot the Louvre! A bas l’originalité, the sterile and assertive ego that imprisons us as it creates. Vive le vol-pure, shameless, total. We are not responsible. Steal anything in sight.” Always endearing, Burroughs!

Jamie Reid: (Laughs) Very Situationist!

GS Artists: No kidding. So, what came to mind when I was reading about your response in 2009 to Damien Hirst threatening an art student with copyright infringement: Are you content to have your own work taken, remade, stolen, exploited and appropriated?

Jamie Reid: But I just think it’s so inevitable. My heart is in the right place. And I just, initially with the whole Brit Art thing, I took great exception to people like Damien Hirst and Tracey Emin saying they were inspired by punk, kinda like they were sort of radical and the whole idea, you had Saatchi and Saatchi, the advertising agency which was half responsible for getting Thatcher into power, taking a whole Thatcherite concept about ‘Everything is for sale’, and just making that the British art scene, turning it into a commodity. And I just see say them as Thatcher’s spawn, I can’t stand it. It’s a complete sort of…I talked to Jane (Simpson) about this. There’s such a monopoly on the art scene here between critics, leading artists, gallery owners, there is a whole social network that you might have to become part of to get any recognition. It’s unbelievable.

GS Artists: The commodification of art has become a disease.

Jamie Reid: One of the things that had a great effect on me was being in Liverpool when it was City of Culture and Liverpool always has and probably always will have an incredible underground and alternative art scene that no longer got a look-in when it was City of Culture. They are prepared to spend 80,000 pounds to get Tracey Emin to stick a sparrow on a pole. And I said, What the fuck! And Jonathan Meades, he did a documentary around that time about the history of Cities of Culture starting in Bilbao. And he’s quite interesting, Meades, because you can’t really put a finger on his politics because he’s quite sort of his own man really. But he started in Bilbao and said from his perspective, he went to every City of Culture, and so what this actually meant, it’s moving all the working class out, tidying up the city centers, using it and art as a means of creating , shopping malls, expensive restaurants, hotels. And he just went through city by city and it’s certainly true that happened in Liverpool.

Jamie Reid: One of the things that had a great effect on me was being in Liverpool when it was City of Culture and Liverpool always has and probably always will have an incredible underground and alternative art scene that no longer got a look-in when it was City of Culture. They are prepared to spend 80,000 pounds to get Tracey Emin to stick a sparrow on a pole. And I said, What the fuck! And Jonathan Meades, he did a documentary around that time about the history of Cities of Culture starting in Bilbao. And he’s quite interesting, Meades, because you can’t really put a finger on his politics because he’s quite sort of his own man really. But he started in Bilbao and said from his perspective, he went to every City of Culture, and so what this actually meant, it’s moving all the working class out, tidying up the city centers, using it and art as a means of creating , shopping malls, expensive restaurants, hotels. And he just went through city by city and it’s certainly true that happened in Liverpool.

GS Artists: There was a very interesting documentary on Channel 4 years ago about how the city centers are designed now, they call it “cookie-cutter”. They’re all identical and they found that all the major stores, for example, we’re all in the same places, in relationship to each other. It was all this kind of surreal replication.

Jamie Reid: And they all look the same.

GS Artists: Obviously intentional, some sort of subliminal drug they’re administering, very strange in any case.

Jamie Reid: That’s very interesting with that whole Situationist thing, which in many ways came out of a critique of the 20th century, well, most architecture presupposes people’s functions within those buildings. And someone said, it’s interesting now even more so, but everyone’s scared when they walk through a city center, never looking up above shop level, everything at the shop level, everything; advertising, shop windows and how people should look up and see what the buildings really are. It’s even worse now when people are all looking at, talking on their phones and tablets. It’s unbelievable.

GS Artists: The dominance of people looking down at their mobile phones has pretty much destroyed much hope of anyone looking up again. That opportunity may be gone forever.

Jamie Reid: I’ve lost someone recently that I loved and work with, a Russian computer artist called Alexei Blinov who died quite recently of cancer, and Alexei, I’ve done projects with Alexei that are totally mind-blowing. He’s one of those people, like he’s come from the future. He’s got amazing radicalised ideas about computers and I did a lot of laser work with him where I did my drawing. He’s been immersed in…this is something that’s going to become quite big news, and in fact it has in Europe already. It’s a Russian film called DAU, which hasn’t opened in Britain yet, but it will, which is interesting in itself. But, Alexei at one point, I mean, he was a computer genius. And he was working with some of the top hackers, I think they were actually Serbian, and they signed him up and told Alexei, throw your computer out the window, get rid of your mobile. And he said why? He said because they’re an alien interjection into our technology, an alien force which is going to eventually take us over by taking, by obliterating all non-use of them so the whole world becomes utterly dependent on them. And even if it’s not true it’s a great science fiction story!

I was pretty much brought up in a sort of spiritual, Druidic background through my family for three generations now and there was always this notion that…I was actually going to do a project with Alexei about it, about the crystals and quartz and stones, particularly in stone circles having memory and certain dance rituals and chanting could evoke the memory of the ancestors, you can actually communicate with your ancestors. And in this country, there is an amazing writer called Nigel Kneale who wrote The Quatermass Experiment, which are just fantastic in themselves, brilliant science fiction stories. He did a BBC series called Stone Tapes, and what I loved about Kneale is he had a great sense of mischief and satire, it was about a really trendy new type sort of graphic design advertising company that was absolutely all the whiz with the first computers, and they decided to get away from it all and move out of London into the countryside. They moved into this big old house in the middle of the Yorkshire Moors – typical, it’s always the Yorkshire Moors – and all their computers started playing up till eventually a few episodes on, people started appearing, ghosts started appearing. And his whole thing then that the building, the stone, had memory. Very interesting. There is so much hidden science we don’t go into.

GS Artists: Crystals have remarkable properties, incredible properties. And, actually, my next question is about this autobiographical film you’re working on with Julian Temple, I understand, about your Druid…

Jamie Reid: Hopefully.

GS Artists: In any case, the general public might be intrigued that you of all people – the famous “punk rock artist” – is a Druid or has Druid heritage. Can you elaborate on your spiritual context and the film project?

Jamie Reid: I don’t know, I mean, it’s only surprising because of the way we analyse and criticise everything. Because, if you think of William Blake, he was political, but he was very spiritual. And there’s a whole tradition in this country that’s completely unrecorded of that. My great uncle, George Watson MacGregor Reidwas head of the Druid order, but he totally immersed himself in the first health foods and things like homeopathy. It’s interesting that people scorn homeopathy, but the Royal Family uses homeopathy and I’ve just never seen it as a problem. I was brought up with a sort of, in a way, it was the Druid tradition, and it wasn’t much more than a complete love of nature and the planet. But I was dragged off at the age of seven on the Aldermaston marches, my parents were great campaigners for nuclear disarmament. It’s only now that some of the truth is coming out about art, even in terms of let’s say American abstract art. A classic example is Mondrian. Mondrian, as we conceive him was invented by postmodern 1920s critics who came up with the term postmodern. Everyone regards him as a painter who did all these geometric colours, shapes and squares and rectangles. Half his work was unseen, he was a Theosophist, he did this massive big triptych of three goddesses. And he was actually using art, he wanted to get to really simplistic ways to create pure energy. He wasn’t going in as a sort of industrialist or postmodern artist at all and so much about our art criticism that is so fucked up like that. You had Madame Blavatsky and the Theosophists in New York, she had a massive influence on American art, even up to Jackson Pollock and it’s only just coming out, these sorts of things.

GS Artists: It’s very interesting the Theosophist connection. I was a very, very keen student and practitioner of Krishnamurti’s teaching, so I know about Theosophy and Blavatsky and the history of Theosophy. Strange, because I was talking to a friend about Blavatsky a couple of days ago, but that’s the universe for you. Let’s face it, everything always happens before it happens. You did touch on the young British artists, God help us and so on, which brought a question to my mind: in your interview in the Guardian a couple of years ago about Hirst and Emin for example, you said there’s nothing remotely shocking about what they do, which I agree with. So where is the cutting edge of art? Does it have one now or is there no future for art?

Jamie Reid: I mean, there’s probably great art that we don’t know about happening worldwide.

GS Artists: True, so true.

Jamie Reid: Things that have had a great influence on me, I’m Scottish, early Celtic art, Aboriginal art, things like that, and it’s only when you really understand the true nature of this sort of art, that it’s full of great love for the planet and nature. I saw a documentary about Captain Cook about a year ago now. And, one, it was interesting because he was completely mad. He was an absolute mad man, loved the cat-o’nine-tails punishment and all sorts of stuff like that. But they asked an Aboriginal elder what he thought of Captain Cook and it just stopped me in my tracks, it’s so obvious but on a timescale, it was unbelievable. He said, look, we’re probably the oldest people, humans who have been on this planet maybe up to 60,000 years. We try to move at one with nature, we have a great love of nature, great respect for nature and the planet and the universe. Captain Cook arrives 250 years ago…and what the fuck has happened since? And it’s so true, I mean in such a short space of time to cause the absolute rape of this planet.

GS Artists: Possibly this is all about us going off the planet, eventually, back to where we came from – wherever that is – some of us, anyway, but that is speculation…

Jamie Reid: There’s so much stuff that surely, they are going to reveal soon. From all sorts of different directions, I really believe that Mars was populated once, maybe two or three times. There are beings that have been on this planet maybe all sort of times, which we don’t know about. Eventually the truth has got to come out.

I used to know a top animator who worked for Spielberg, he was working on a project, believe it or not about the Arabian Nights that never got finished because of the politics of it. But anyway, Spielberg was convinced – he had personal conversations with Spielberg and Spielberg was basically saying there was a whole element of what he does which was to prepare people for things that might possibly happen.

GS Artists: As a huge fan of Close Encounters, I like to think that was based on true events or an outline of events. It’s prophetic. Even Gene Roddenberry who created Star Trek said very near his death, I can finally tell you that it’s based on contact I had with extra-terrestrials.

Jamie Reid: Interesting guy, isn’t he?

GS Artists: A visionary, he was doing important messaging to humanity if it would only listen for once but he tried anyways, and we shall see. Which is an interesting time to mention the first time I came to Britain, which was a great year to arrive as you will understand: 1977. It was just incredible in London at that time. And of course, you would have been part of that narrative that I experienced. Anything seemed possible, it was the most phenomenal atmosphere to drop into. In 2020, anything may still be possible and plausible, but what are the chief differences to you between that world in 1977 and the one we’re inhabiting now? And how, more importantly, is it impacting your work now?

Jamie Reid: I think there is more, far more control on people’s thoughts and actions than it’s ever been, which has gradually been chipping away since the 1970s. I also think I’ve had a really interesting time. I’ve been in a hotel for about a year now and I’ve got quite addicted to listening to BBC Radio 6 and even last year they had a whole lot of pre-recorded interviews of Malcolm McLaren and it’s been very odd laying here listening to Malcolm speak for an hour; I have forgotten how fucking brilliant he was, not just talking about punk. I also had the realisation that he and I had a complete trust of each other. He never questioned anything about any artwork I did, I never questioned any directions he was taking. I’ve kept very quiet from my end about that time. But I think the Pistols and, to some extent, punk wouldn’t exist without the political experiences me and Malcolm had in the late 60s and our understanding of Situationism and putting it into practice, and positioning it in popular culture, That’s what we tried to do. And I think getting God Save the Queen to number one in 1977 is proof of that.

Jamie Reid: I think there is more, far more control on people’s thoughts and actions than it’s ever been, which has gradually been chipping away since the 1970s. I also think I’ve had a really interesting time. I’ve been in a hotel for about a year now and I’ve got quite addicted to listening to BBC Radio 6 and even last year they had a whole lot of pre-recorded interviews of Malcolm McLaren and it’s been very odd laying here listening to Malcolm speak for an hour; I have forgotten how fucking brilliant he was, not just talking about punk. I also had the realisation that he and I had a complete trust of each other. He never questioned anything about any artwork I did, I never questioned any directions he was taking. I’ve kept very quiet from my end about that time. But I think the Pistols and, to some extent, punk wouldn’t exist without the political experiences me and Malcolm had in the late 60s and our understanding of Situationism and putting it into practice, and positioning it in popular culture, That’s what we tried to do. And I think getting God Save the Queen to number one in 1977 is proof of that.

GS Artists: The kind of relationship you described that you had with Malcolm McLaren reminds me of Burroughs and Gysin. The quasi-magical “Third Mind” creative process and bond.

Jamie Reid: Malcolm always claimed he had Aleister Crowley’s ring! Again with Malcolm, it’s only when you hear people from other situations talking about him, I mean, in my mind he is possibly one of the greatest artists of the 20th century. But you’re never going to get art critics being able to understand that because I heard people like New York rappers singing Malcolm’s praises, not saying he invented rap but saying if it wasn’t for him doing Buffalo Girls, it opened up the whole fucking picture for us. The same with the things he did in South Africa with African music with Trevor Horn, you get African musicians saying the same thing. What he did with opera and Madame Butterfly. To me every bit as important as the Pistols in many ways. But he’s not going to be seen like that.

GS Artists: The term for someone like that would be a Renaissance Man, he was a Renaissance Man of his time.

Jamie Reid: A great bullshitter.

GS Artists: Well, that always helps if you’re a Renaissance Man.

Jamie Reid: (Laughs) Told a great story.

GS Artists: He had his own powers in terms of propaganda certainly, no question about that, quite a genius, really. He played the British media and public like a violin.

Jamie Reid: With my Druid, aboriginal head-on it’s an awful thing to say but I almost think the planet has had enough of us. You know: You’ve had your chance, you blew it.

GS Artists: Humans are very vain. And we think due to ego that we’re the most important thing on the planet, which is where all the panic about the climate crisis and so on really comes from: we don’t want to die. The planet itself, it’s been around a long time, it’ll be around a lot longer, it will be fine whatever happens to us. I watched a Storyville documentary about Jonestown which was fascinating. They were saying within less than ten years, the entirety of Jonestown had been completely reclaimed by the jungle, and that’s just a microcosmic snapshot of the process. It’s humbling and comical.

Jamie Reid: There are all sorts of sides to work I’ve done every bit as important as the punk, agitprop work, and it’s funny you mentioning Jonestown because I’ve worked with a heavy metal band, who are half Dublin, half Glasgow, called The Almighty. They did an amazing record called Jonestown Mind and they’re one of those bands that could play to quarter million people in Brazil and hardly anyone has ever heard of them here. I did a whole album and a single project with them. I’ve also been working for getting on 15 years now integrally with a band called Afro Celt Sound System, which is a fusion of Irish, Scot, Welsh music and African music built on a realisation there is a common thread through them all. And that came out of a whole project I did, creating interiors of a recording studio in Shoreditch called The Strongroom. And it is was like being practical with magic. I’m involved at the moment doing a book with someone about magic and art…and I did a studio design that was totally based on the four elements. It was aligned with earth was north and fire was south, water was west and air is east and it was all using symbols and astrology and all sorts of stuff, purely to create a space that could encourage the making of sound and music. And it works. Another level, I’m quite a big fan of the Prodigy, and they used to use that recording studio. And Keith, the lead singer – he died recently – I was sending him all this bullshit about my beliefs and magic and spirituality. He said, Jamie don’t give me all that fucking bullshit! I said, why? He said, it’s just a brilliant space to work in, it just an uplifting space to work in and it was true, it is.

I suppose it links back to my beliefs in Situationism and the situation with cities and architecture. Buildings could be the most inspirational places; I have been quite involved with my painting about how you can use colour for healing and how you can use sound for healing. And there are all these fields we don’t know about. And on an almost frightening level it actually ties in with that almost complete disrespect for nature. Look at the number of words to do with nature that are falling out the dictionary now. And it’s like our analysis of horticulture and farming, it’s like, what is a flower and what is a weed. Most of the things we define as weeds are in fact healing weeds, plants that used for healing. We had things like Lungwort, and there’s so much of it. And it’s a lost art almost. Yeah, anyway, I’m rambling…

I told you that working with Alexei Blinov, a Russian artist, we were just immersed in starting a project which we were going to do together, which we actually got down on paper. And it was about how my paintings, Alexei was going to use and create computer machinery to actually turn my paintings into energy. And it was based on the physicist who worked in the 19th century. There’s another Victorian scientist who did some wild stuff and it’s such a shame to me that we never had a chance to do it. But we got it on paper. And it’s quite interesting. But anyway, that’s enough.